In all builds

If you elect to “shuffle play” something, the thumbs purely mean “add to queue” or “reject” and have no other effect. Shuffle play is simple randomized play of the content that you chose, no added flavors or ingredients.

For Library Radio (or 1.5), not the new cloud-based Roon Radio

The thumbs up on the queue screen purely means “add to queue” and has no longer effect.

The thumbs down on the queue screen means “reject” and slightly adjusts the current radio session only. There is no long lasting effect.

For the new, cloud-based Roon Radio released in 1.6–

Give honest feedback to the algorithm and trust us to do the best thing with it. It is designed to learn from everything you do while it is active. It is not going to over-react and ban John Coltrane from your life just because you thumbsed down something once. There is no way for you to ruin your own experience with those thumbs,

The thumbs are primarily used to improve large-scale models that are shared amongst everyone. They help the algorithm learn how to make better picks for everyone. They do not immediately or drastically update our model of you as a listener in any way that is worthy of concern.

The number of aggregate feedback items we’ve collected so far is already very large™ compared to any one user’s feedback, and especially compared to any single action that you take, and the feature has been live for less than five days. You do not have enough statistical power over the algorithm as one person to skew it in any meaningful way.

The Value

I love Anders’ notion of value above. It’s a great way to think about it…so let me frame radio in those terms.

There are three goals for Roon Radio: to have lots of people enjoy it, to minimize negative feedback, and to encourage people to grow their libraries. Some of the first things I looked at after the algorithm was live for a few days was the amount of usage it was getting (both in absolute terms + per-person), the proportions of positive/negative/no feedback, and the number of library adds that result from radio play.

The algorithm is good if people use it a lot without complaining very much and their libraries are growing as a result. This is the Value we are trying to maximize.

A more concrete example

Let me give a simple example of a way in which the algorithm might learn. There are more complex ways too, but they require more mathematical foundations than I haven’t thought through how to explain here, so lets start with a simple kind of learning that we can explain in mostly familiar terms (there are more indirect/mathematically intense models inside of Roon Radio…perhaps I will explain some of them one day, but for now, lets start with something more accessible).

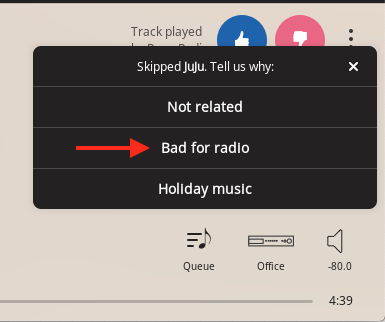

For this example, lets start by considering the subset of tracks that Roon Radio has picked for anyone at any time in the past which have also received the “bad for radio” feedback.

(Just to make my point, I actually clicked “Bad For Radio” after taking this screenshot, even though I love this song…because it. doesn’t. matter. I am just one person, not big enough to screw up the data.).

Let’s further focus on the “This Track is bad for radio” feedback. Given enough time, every track is going to get some. Maybe someone particularly hates Stairway To Heaven or has a particularly narrow view that radio should only play 3 minute songs, or whatever. So they say “Bad for Radio” to us. That’s fine.

We might start by disregarding all tracks that have been played very few times or only received a small number of feedback events because we expect data for those to be too noisy. So maybe we only look at tracks that have at least 10 feedback events and have been picked more than 100 times (more likely we would not use absolute numbers to make this more robust to the data set changing size).

First we must establish a baseline by looking at the mean or median number of “Bad For Radio” feedback events per track in that data set. This tells us how much “bad for radio” we should expect for a typical track.

I would expect a “u-shaped” distribution–a concentration of tracks that have little/no “bad for radio” feedback, and another concentration that have a high proportion of “bad for radio” feedback, and a relatively weak amount of data between those extremes, but would definitely make the plot to test this hypothesis if we were actually doing this  .

.

Once we understand the distribution, we might be able to come up with a rule. For example, “any track that is two standard deviations from the mean in its proportion of “bad for radio” feedback is probably “bad for radio” for everyone”. Essentially, we have come up with a very simple model for predicting future “bad for radio” feedback. We could use that model to make it much less likely that we pick those tracks.

We could also eliminate them entirely, but then there would be no way for a track to slowly redeem itself over time. I think if we were to build this system in practice, the elimination would be probabilistic, like “reduce the likelyhood of picking Despacito based on how far from the mean it is”. This would allow the algorithm to smoothly reduce the prevalence of a track as feedback comes in, but without making a rash change all at once. One feedback event moves the needle an insignificant amount, so there isn’t ever a place where the straw breaks the camel’s back and the algorithm has a “step change” in its behavior as a result of one increment of data showing up.

Here’s a refinement to that idea–what if a bunch of people vote “Bad For Radio” on Despacito because they are temporarily exhausted of it. So many people hate it that it is being picked one millionth as often as before (e.g. never, for practical purposes). Is that good?

I say no–we shouldn’t ban it forever. Its un-welcome-ness is a temporary situation, so maybe we should do something to weight the feedback based on when it arrived. More recent feedback has a stronger weight attached to it, but feedback from a year ago is only half as informative–something like that. Techniques like that give the system extra robustness and a self-healing quality. If people continue to hate Despacito, it will continue to meet the model criteria for a “bad for radio” track. As people stop hating it, it will slowly return to normal pick probability.

To be absolutely clear–I am not describing the actual guts of Roon Radio. This is more like a brainstorming session about what to do with “bad for radio” feedback that is meant to help you understand the long torturous path between a single feedback event and tangible impact on the algorithm’s behavior.

Over time, as we collect more data, we can add more models to the system to make it smarter, or enhance existing models to make them perform better. Most of those models are data-driven, and will slowly change their exact behaviors over time based on what the data teaches them.

It’s actually too early in our feedback gathering to have a model like the above. 5 days into Roon Radio, we don’t have enough data collected to make that work. As of today, “bad for radio” does nothing at all other than take note. In a month or three, we will have enough data to actually implement an idea like the above.

Zooming out…briefly

I hope that helped. This is a complex topic, and I could write at least as many words about how to develop a good mindset for understanding all of the machine-learning systems that we interact with daily and having good intuition of how they work and what they are/aren’t good at doing.

Think about self-driving cars for a second–humans often cause accidents out of inattentiveness or failing to see something or by being drunk. Self-driving cars are much better than us at paying attention and at keeping their eyes on the road and they can’t drink. But they are worse than a human with tracking a lane when the road markings are ambiguous or in poor condition or when there is a lot of snow on the road. They don’t make some of our most common mistakes, but they also make some “easy” mistakes that we don’t make.

This kind of gap between what the humans can optimize for and what the machines can optimize for is key to understanding all of these systems–the goal isn’t to make the same radio stream that a DJ does. That’s a distinct idea, with distinct value, best judged differently. The value is in a radio feature that a lot of people enjoy engaging with a lot, annoys them as little as possible, and that helps them find new music delivered for a tiny fraction of the cost of a 24/7 personal DJ. That’s it.